Biogen warps the FDA on Alzheimer's drug

The FDA discards its outside experts, which it never does, to approve the first new Alzheimer's drug in 18 years, after Biogen flexes celebrities and marketing.

For Samuel L. Jackson, it’s good work when you can find it. The corollary is, “Anyone who tells you money can’t buy happiness never had any,” he’s quoted. So when drug maker Biogen and the Alzheimer’s Association came calling, the hardest working actor in Hollywood answered the phone.

The FDA, stunningly, discarded the overwhelming consensus of its outside advisory panel of medical experts, and gave Biogen’s new drug the green light. The FDA pretty much never does that. So why did it work this time? Was it the earnest desire to see some progress on Alzheimer’s? Was it marketing pressure, or was it some buddy-buddy arrangement between Biogen and the drug regulator?

Jackson didn’t do it for the money, because the gig paid nothing. The payoff is that Biogen believes it might have the beginnings of a miracle drug, the one we’ve all been waiting decades to see. It’s called aducanumab, and it had a big problem: the FDA was not going to approve a drug that didn’t meet its standard of two trials with provable results.

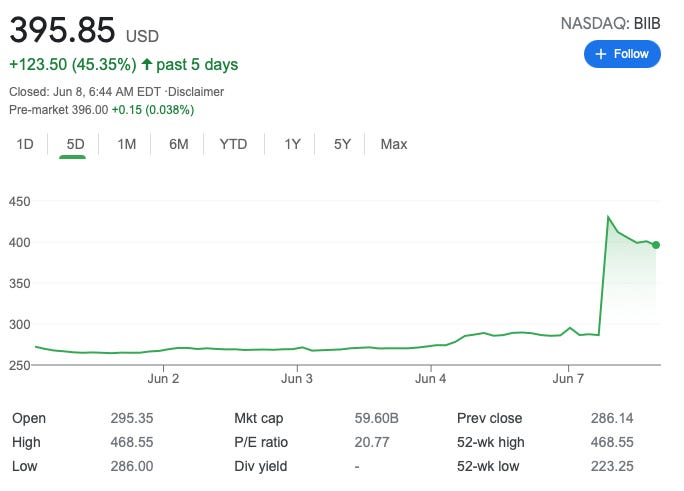

And when I say “payoff,” I mean that Massachusetts-based Biogen has staffed up, adding 1,700 employees in 2020, to support the drug it will market under the name Aduhelm. Clearly, they bet on approval, despite the less-then-positive test results. Shareholders (and corporate executives) stand to make a pretty penny from the drug, which the company has not yet priced. Biogen’s (BIIB) stock has soared, gaining $123.50 per share, or over 45% in the past five days.

It’s not the first time a drug company has lobbied the FDA. According to Fierce Pharma, an industry publication, Sprout Pharmaceuticals seeded an astroturf campaign for Addyi (the female version of Viagra), and Sarepta leveraged families with Duchenne muscular dystrophy to promote the drug Exondys 51. Both won approval. But in those cases, the FDA did not reject the opinion of its outside advisors.

And also, Alzheimer’s Disease is a hundred times more of a front-and-center problem for Americans than women’s libido or, unfortunately, muscular dystrophy, which has had a long history of expensive research and high profile funding.

As America’s population ages, we all worry that one of us might get the disease, a long, painful farewell with a very unsatisfying end, for the sufferer, and especially the family. My mother died of Alzheimer’s after a decade-long fight. She took Aricept, and it kept the disease from progressing (it did not reverse) for a number of years. But when it stopped working, she declined quickly. My step-father cared for her, right until the very end. In fact, he spent so much of his time caring for her that he neglected his own treatable bladder cancer, and it killed him. They died 16 days apart.

Alzheimer’s sucks. Nobody wants it cured more than me, and the thousands of others who yearn for a working treatment. Any treatment.

But is Aduhelm the answer? Not everyone—experts—thinks so. The Boston Globe quotes some notable skeptics.

Dr. Jason Karlawish, co-director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Memory Center, said he understands the urgency behind the push for Aduhelm but believes the data do not clearly show that it works.

“Desperation should drive funding for scientific research and not drive the interpretation of scientific data,” he said.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and one of 10 experts on the 11-member advisory committee that resoundingly recommended rejection of the drug, said regulators have “set a dangerous precedent for the low level of data needed to support efficacy in treatments” for Alzheimer’s.

Further, some accuse Biogen and the FDA with “cherry picking” results of the clinical trials, which even the FDA admits have “residual uncertainties.” From the New York Times:

“The data included in the applicant’s submission were highly complex and left residual uncertainties regarding clinical benefit,” the F.D.A.’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni, wrote on the agency’s website.

Biogen conducted two trials, and shelved the drug in 2019, after the second trial appeared to show no improvement.

The crux of the controversy over the drug involved two Phase 3 trials with results that contradicted each other: One suggested the drug slightly slowed cognitive decline while the other trial showed no benefit. The trials were stopped early by a data monitoring committee that found the drug didn’t appear to be showing any benefit. Consequently, over a third of the 3,285 participants in those trials were never able to complete them.

But then, the company claims it took another look at the data, and that the problem with the second trial was dosage, not the drug itself. It offers scant evidence its claims will pan out as true.

Biogen later said that it had analyzed additional data and concluded that in one of the trials a high dose could delay cognitive decline by 22 percent or about four months over 18 months. In the trial’s primary measurement, the high dose appeared to slow decline by 0.39 on an 18-point scale rating memory, problem-solving skills and function. A lower dose in that trial and high and low doses in the other showed no statistically significant benefit over a placebo.

I would love for the drug to work. It’s supposed to lower the level of amyloid plaque, found in the brains of Alzheimer’s sufferers. This could have the effect of actually rolling back some of the more debilitating aspects of the progressive disease. A miracle drug. But it has risks, too.

The risks with aducanumab involve brain swelling or bleeding experienced by about 40 percent of Phase 3 trial participantsreceiving the high dose. Most were either asymptomatic or had headaches, dizziness or nausea. But such effects prompted 6 percent of high-dose recipients to discontinue. No Phase 3 participants died from the effects, but one safety trial participant did.

Similar side effects have occurred in trials of previous amyloid-lowering drugs, but doctors consider them manageable if a patient is evaluated regularly with brain scans. Still, even supporters of approval said that conducting such safety monitoring was more difficult when not done in the carefully controlled regimen of a study.

How many patients, or their families, are going to take a risk in using a newly-approved drug that will require constant monitoring, brain scans, and dosage adjustments? Some might benefit, and some might be pursuing false hope.

How many doctors are willing to give patients what they’re hoping for, only to have those hopes dashed if the drug doesn’t work? But if it does work, even for a percentage of patients, it could be a massive breakthrough.

The problem here isn’t that Biogen is an evil company selling snake oil. The problem is that the FDA, like all of us, us being swayed by hopeful emotions, slick marketing, public opinion, and not swayed by its own medical experts. That’s troubling.

It’s one thing to have “Operation Warp Speed” on a new vaccine. The companies that produced the vaccine knew how to make it. Within a month of the first case, Pfizer knew how they’d attack the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The purpose of “Operation Warp Speed” was to quicken the path from lab to arms for as many drug makers as possible, at a massive scale. It worked.

Aduhelm is not “Operation Warp Speed.” Alzheimer’s is not COVID-19. It’s a killer, for sure, but it’s a long, slow, painful killer. And the first thing to die is hope.

The fact that Biogen got the FDA to bet on its own hopes, while making fat bank on the approval, bothers me. What will happen with the next drug, maybe one that treats heart disease? Or some new cancer treatment? Will our ability to hope for miracles, coupled with a few calls to celebrities like Samuel L. Jackson, warp the FDA’s ability to remain grounded in data, the scientific method and sound medical advice?

If Aduhelm works, great! But the next bet the FDA makes might not pay off. We know what happens when the public loses faith in government regulators, especially in the complex field of medicine and drugs. We need to pray and hope the FDA made the right bet here, and they’re not warping themselves to failure.

If you haven’t subscribed to the Racket yet, click the button below to do so while it’s still free. And remember, with the Racket you get MORE than what you pay for!

You can also find The Racket News (@newsracket) on Twitter and Facebook. Join the discussion online with our Racketeers Facebook group.

Follow The Racketeers on Twitter: Jay, Steve, and David.

As always, we appreciate shares. If you see something here that you like, please send it to your friends and tell them that all the cool kids read the Racket!