Hate is no picnic, even if you pack a lunch

History teachers always say that we need to know the past to prevent it from happening again. Does this view sound like one that someone could use to prevent it from happening again?

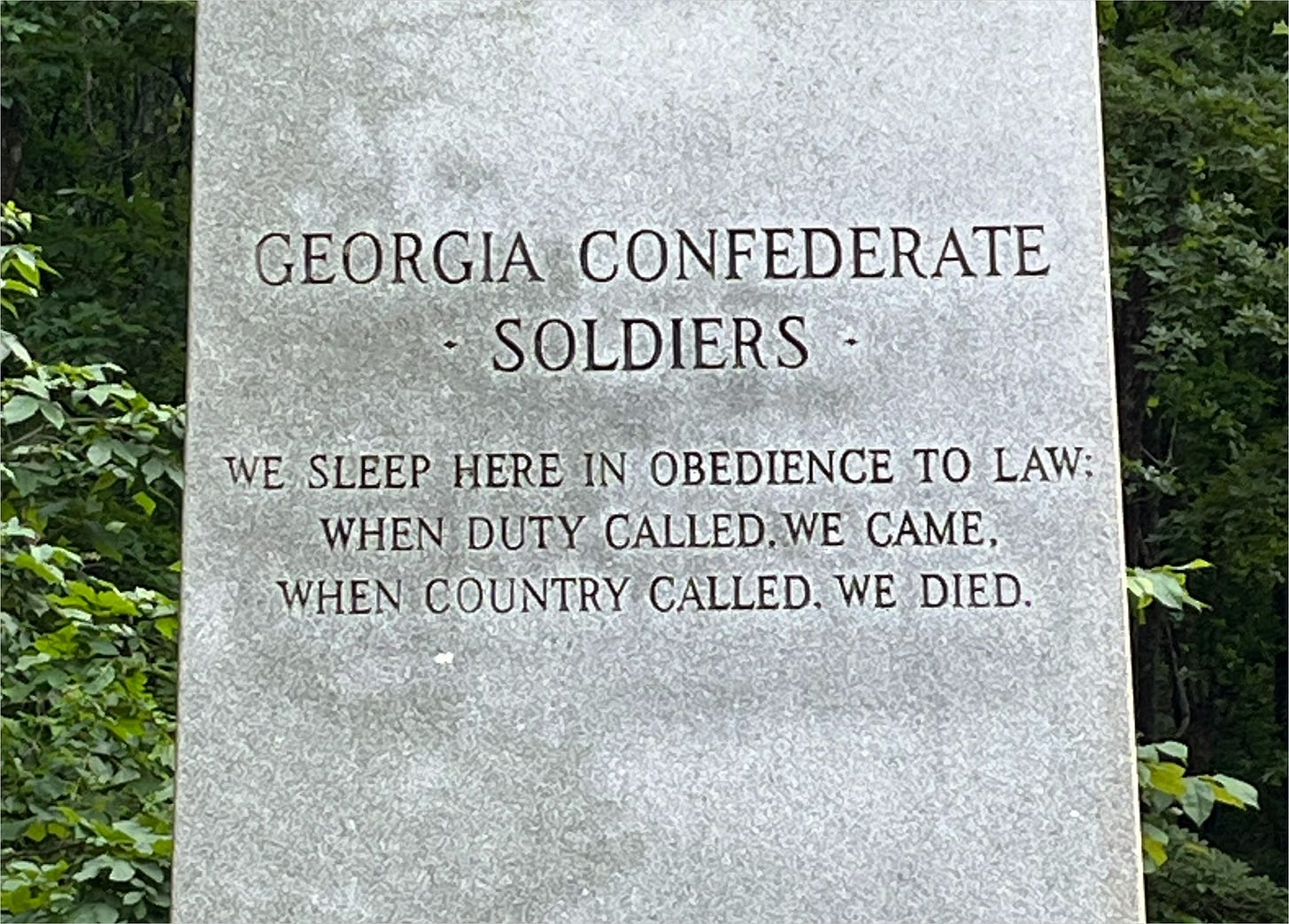

Yesterday, my oldest son, Sam, and I spent some time at the Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield. That puts me in the mood for some history. Get out your walking shoes and join us (yes, Sam pitched in here), if you’re willing.

It was at Kennesaw Mountain that Gen. W. Tecumseh Sherman faced Confederate Gen. Joe Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in June, 1864. Johnston had only replaced Gen. Braxton Bragg (namesake of the former Fort Bragg, now named Fort Liberty) the previous November, after Bragg resigned following his loss of Chattanooga to Sherman.

Sherman spent nearly six months building 70 days worth of food, ammunition, and fodder, filling the warehouses in his new forward logistics base in Chattanooga, a major railroad hub. He did this by commandeering every steer, and every piece of rolling stock from Ohio down to the Tennessee River in Chattanooga. Nothing rolled on the rails, and no cattle moved, unless it was moving what Sherman wanted, to where he wanted it.

On the opposing side, Johnston, who was quartermaster of the United States Army for two years before the war, refused to attack Sherman’s superior forces without reinforcements, which were not available from Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, due to Jefferson Davis’s plan to hit the north on its own territory. Before the war, Johnston outranked every other serving U.S. Army officer who resigned and took up arms against their country. Lee was a colonel; Johnston was a brigadier general. Neither Lee nor Davis were particularly fond of Johnston, who had a tendency toward being “a difficult and touchy subordinate.”

“Cump” Sherman (his given name was Tecumseh; a clergyman added “William” because it was not seemly for a white man to be christened using an Indian name; Sherman never used the English name) was a soldier and a student of war. He studied Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz and the idea of “total war” where the economy and logistics of the enemy were important, and fair targets. Sherman was an atheist at heart, and a professed agnostic; fighting for God was not an arrow in his quiver. He fought for the army for which he had given his oath. A gentleman’s honor was not one of his finer points, but as a pragmatist, Sherman knew how to bring and win a war.

These were the two who faced off at Kennesaw. Johnston wanted to stop Sherman’s 100,000-man army from reaching Atlanta, using a series of blocking maneuvers, moving his 50,000 rebels into strong positions. Sherman was determined to reach the city, for its railroads and its value as a logistical hub to the Confederates. He sought to avoid pitched battles.

Let’s step back three and a half years prior to the events at Kennesaw Mountain, back to the start. At the inception of the American Civil War—nothing happened.

Shortly after Abraham Lincoln’s election, on December 20, 1860, the elected legislature of South Carolina voted for secession. From January to February 1, 1861, six more state legislatures voted to secede from the Union (Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas). Upon secession, southern senators and congressmen departed Washington, leaving their seats vacant. It wasn’t until July (after hostilities commenced) that 10 southern senators would be formally expelled. The House of Representatives expelled only three members; two from Missouri and one from Kentucky.

Militarily, nothing happened until April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter. Before then, Confederates under Jeff Davis were building their army, buying materials from commercial producers (many of them in northern states) and conducting business as before the war, but with the purpose of completing their separation. Davis didn’t believe in a command economy, but was a micromanager of things he did believe in (like directing military operations). That would prove to be a disastrous combination.

President Lincoln’s main concern was building an administration, while protecting Washington from possible rebel action. Gen. George B. McClellan built a beautiful army around the capitol, and showed it off with pride, as his troops loved him. Spit, polish and endless drilling marked the U.S. Army, which McClellan was unwilling to commit to fighting his fellow countrymen unless he could parade victoriously through the streets of the confederate capital without a scratch. (The capital wasn’t moved to Richmond from Montgomery, Alabama until May 8, 1861.)

For nearly three months, Lincoln hounded McClellan to take action, while the Navy blockaded all ports under the control of the states which seceded. Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase recommended a former instructor of military tactics at West Point, his friend Captain Irvin McDowell, to lead a decisive attack to end the rebellion. Newly-promoted Brig. Gen. McDowell, in his first foray as a field commander, reluctant but under political pressure, led 28,450 troops to capture Richmond.

As the men marched out of Washington, a train of spectators followed. The American Battlefield Trust published an account from Centreville, about five miles from the battleground—known as Bull Run—in Manassas.

Near Centreville, Capt. John Tidball witnessed a “throng of sightseers” approach his battery. “They came in all manner of ways, some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback and even on foot. Apparently everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion. It was Sunday and everybody seemed to have taken a general holiday; that is all the male population, for I saw none of the other sex there, except a few huckster women who had driven out in carts loaded with pies and other edibles. All manner of people were represented in this crowd, from the most grave and noble senators to hotel waiters.”

The audience couldn’t see a whole lot from their position through the smoke and fog of battle, though some notables approached a lot closer. Rhode Island Gov. William Sprague rode with his state’s adopted hero, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, and had two horses shot out from under him. New York Rep. Alfred Ely, from the 29th Congressional District (Saratoga, Warren, Washington counties) got too close to rebel lines and was heard shouting “On to Richmond!” He got his wish—the 8th South Carolina infantry captured him and shipped him to Libby Prison, where he spent five months in company with his southern hosts.

Of course, the crowd didn’t know how badly the battle was going. Accounts tell how one excited lady exclaimed “I guess we will be in Richmond tomorrow!” An officer rode up and told encouraged the cheering throng: “We have whipped them on all points.” They found out differently when the federal troops came in full retreat, rebel cavalry on their heels.

Ultimately the curiosity-seekers got caught in a stampede of retreating Union troops. McCook desperately raced back to Centreville with his son Charles, who had been mortally wounded while visiting and separated from his unit, as Confederate cavalry attempted to intercept the Union retreat. Photographer Mathew Brady was caught in the congestion at the Cub Run bridge. Congressman [Elihu Washburne from Illinois] tried in vain to rally the panic-stricken mob of soldiers near Centreville, but most of the civilians joined, if not led, the flight back to Washington and escaped unharmed.

By the time the war had progressed to the Appalachian foothills outside Atlanta, few civilians had any interest in gazing at the spectacle of battle.

Sherman and Johnston’s troops clashed from June 19 to June 27. Tactically, the Confederates won, inflicting about 3,000 casualties on the federals. Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s best troops in IV Corps, along with Gen. John M. Palmer’s XIV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland could not penetrate Confederate Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s strong entrenchments and barricades. At Cheatham Hill, Brig. Gen. George Maney’s Tennesseeans held under an immense artillery barrage and assault by Col. Daniel “Fighting McCook’s” men. McCook was killed yards from the enemy; the federals fell back, so close that the rebels were fighting with thrown rocks—in a place named the “Dead Angle” by the men who fought there.

The U.S. Army did not destroy the Confederate Army of Tennessee at Kennesaw Mountain. But that was not their objective. Johnston’s army did not stop Sherman from his approach to Atlanta: by July 2, the federals had maneuvered around the left flank, which forced another movement toward the city. The south achieved a tactical victory at Kennesaw Mountain, but the federals won the strategic victory. Johnston wanted to delay and deflect Sherman’s attack, and a frustrated Sherman briefly took the bait at Kennesaw Mountain.

Months later, the Confederates briefly recaptured downtown Kennesaw, then known as Big Shanty. Sherman had already crossed the Chattahoochee, and Gen. John Bell Hood (namesake of the former Fort Hood, now named Fort Cavazos) ordered Gen. A.P. Stewart (no relation to Gen. Daniel Stewart, namesake of Fort Stewart and great grandfather of Teddy Roosevelt) to retake the town and destroy the railroad lines, which were being used by Sherman to resupply federal troops.

(Going down another rabbit hole: the roles were reversed 27 months earlier. Union army volunteers—spies—along with a civilian scout, devised a complicated, half-baked operation to hijack a Confederate locomotive. They meant to capture it in Marietta, but missed the opportunity, catching up to the train in Big Shanty. Their plan was to destroy as much rail track, bridges, and telegraph lines as possible, running north through Georgia into Chattanooga. The Confederates chased The General, the stolen engine, for 87 miles using another locomotive, The Texas. It became known as The Great Locomotive Chase, and a movie was made about it. You can see The General at the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, in downtown Kennesaw. The Texas was moved to the Atlanta History Center in 2017.)

It might seem like interesting history now, even amusing stories, but hate always has an audience. Connecting those events 160 years ago to today, it seems unlikely that our country could sink into another civil war. (Or does it?) The facts are simple. When our political divide gets wide enough that extremist candidates are preferred to those who can work with “the other side,” and hatred for political enemies is preferred to any kind of reasoned compromise, that’s a recipe for sliding into a more formal division.

Peggy Noonan recently penned an essay titled “We Are Starting to Enjoy Hatred.”

But it really is something that we’re so estranged we know nothing of the other side’s lives, and because we know nothing even our insults are lame and need updating.

The class aspect of the big estrangement portends nothing good. America has been navigating its way through issues of class since its beginning; it is text or subtext of the country’s great novels. Now it is emerging in a new way in our politics, one more laden with meaning and encouraging of unashamed judgment.

I said I sensed people are enjoying their political hatred now. Why would that be?

Noonan called this a tragedy in the making, but couldn’t offer any suggestion how to “turn things around.” She did advise to “ease up,” “slow down our desire to look down,” to be “a little more generous,” and to stop “enjoying our hate so much.”

I think maybe a tour of some Civil War battlefields would help do the trick. Not some movie depicting battle as “glory” or “honor,” but the reality of where hate leads. The Civil War didn’t start with the battle at Fort Sumter. It didn’t start at Manassas. It started when politicians elected for office at the state and federal level decided to take action due to an election result they couldn’t live with. Now don’t get me wrong: slavery was evil and needed to end. But the southern states chose to continue their policy of slavery at the expense of the Union, and Lincoln held the survival of the Union—as an institution and a nation—as sacrosanct and worth 600,000 lives spent preserving it.

A paragraph from my oldest son, Sam:

When in the eighth grade, the board of education decided to forgo the average “social studies” class and instead, make the students learn about Georgia history. This was a change in curriculum that had a great impact on my knowledge, not on the Civil War, but on the modern view of it. The Civil War has been a cause of strife in the U.S. for an extremely long time. We heard it mentioned when we learned about the great depression, the civil rights movement, and today. If you have ever seen a rebel flag flying in the south (something I have seen a lot) then you have seen what one view of the war is. A view that many have called heritage, can easily turn into a view of hate. And when taught by the government, a view of disconnection and disregard can be formed. In the eyes of the D.O.E., the Civil War is as follows: Compromises, Election, Secession, War starts, Emancipation Proclamation, Sherman marches to the sea, End of war, Reconstruction. Shallow waters. History teachers always say that we need to know the past to prevent it from happening again. Does this view sound like one that someone could use to prevent it from happening again?

Back to Steve:

The crowds who followed McDowell’s men out of Washington to a hillside near Bull Run thought they were just spectators at an easy win to crush the rabble-rousers. But the south had spent time and millions of dollars preparing for a real war. Nobody on either side thought it would go on for four years and cost as much blood as it did.

Today, we’re political spectators, watching as states and federal elected officials flirt with the kind of extremism that brought us to war 160 years ago. The crowds at Manassas found out the hard way, seeing the bloody, fleeing federal troops retreat through them to Washington.

It seems we are, as Noonan wrote, enjoying things a bit too much. We should all take a trek through a battlefield, picturing the blood, the smoke, the horror of war, before we cast our next ballot. I am afraid as we careen toward a bleak political future rife with violence and hate, that our impulse will not be to recoil, but instead to pack a lunch.

SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTS: You can follow us on social media at several different locations. Official Racket News pages include:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NewsRacket

Twitter/X: https://twitter.com/NewsRacket

Mastodon: https://federated.press/@RacketNews

We aren’t on Threads as a news page yet, but both David and I have personal accounts there:

David: https://www.threads.net/@captainkudzu71

Steve: https://www.threads.net/@stevengberman

Our personal accounts on the platform formerly known as Twitter:

David: https://twitter.com/captainkudzu

Steve: https://twitter.com/stevengberman

Jay: https://twitter.com/curmudgeon_NH

Thanks again for subscribing! Don’t forget to share us with your friends!

Tell Sam good job. I'm raising a couple of history nuts (I won't say history nerds although that's how I describe myself.)

I used to love the Great Locomotive Chase move, which starred Fess Parker aka Davy Crockett.

Great read and in my opinion, the header is one of the top three in my lifetime. Kudos.