How we can avoid Asimov's AI paradox

There may be some merit to the discredited “parable of the broken window.” Keeping some jobs for the sake of work in an age of AI-powered prosperity is worth considering.

Canadian professor and AI pioneer Geoffrey Hinton worked for Google, helping to design and train their Large Language Model AI software based on OpenAI’s latest generation. He worked there until this week, when he left to join the chorus calling for a responsible pause in LLM AI deployments. I won’t call it a pointless gesture, but it’s not going to be enough. Flesh and bone humans being what we are, capitalism and international competition for scarce resources will win the war against responsible AI.

The pitfalls of LLM have been discussed at length (just read Gary Marcus, a top AI expert and critic of LLM, for the litany). These programs don’t “know” anything. They are simply language models optimized to communicate in a style that humans find familiar. That in itself poses a danger, as culturally, we’ve gotten used to receiving search engine answers from websites like Google, so we tend to trust what spews out after typing in a search box more than we should.

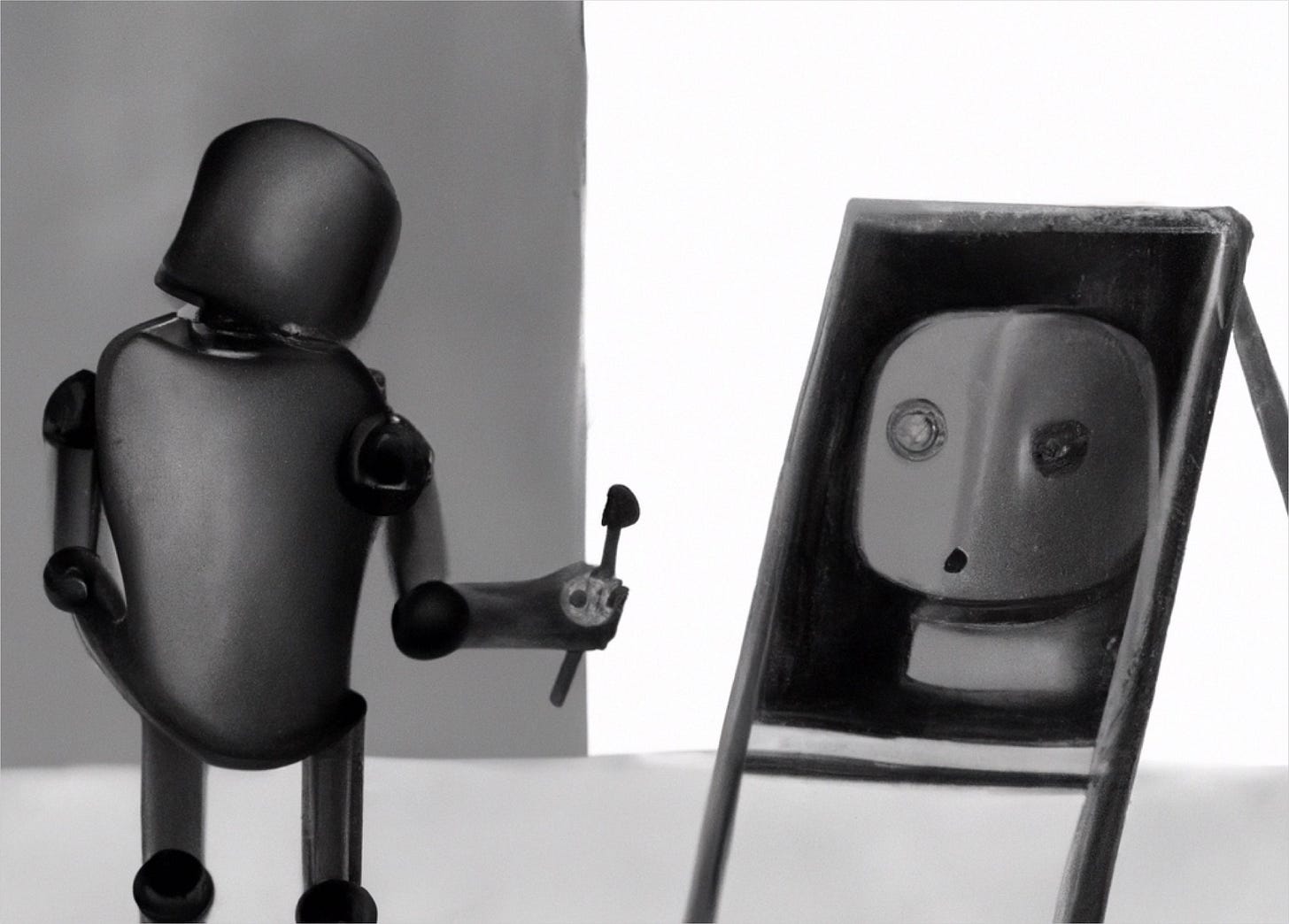

LLM AIs such as Google’s Bard, Microsoft’s Sydney (Bing Chat), and OpenAI’s ChatGPT suffer from the same issues: they hallucinate, making up answers that sound good but are flat wrong; they get basic arithmetic and logic wrong unless they have the answers already present in their training codex; they don’t make reasonable choices when presented with problems they haven’t seen before or been trained to answer. They are far, far from the Isaac Asimov “I, Robot” Three Laws, which offered a ground state philosophy for his sci-fi AI to make sense of the world.

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Where Asimov uses the word “robot,” he really means AI, because a “robot” in the sense of the industrial machines Elon Musk uses to manufacture Teslas in Texas, is only a “robot” because it uses robotic parts and motions. We’ve had those kinds of robots for decades. Asimov’s robot is an AI-powered, independent machine with intelligence and it generates its own will to perform tasks.

The LLM AIs currently deployed on the Web do not understand—are not capable of a ground state philosophy—Asimov’s Three Laws. They do not obey those laws, despite having safety systems deployed between the user and the AI. AIs have led humans toward poor decisions—even suicide. Following today’s LLM AI’s advice is dangerous.

However, a properly trained LLM AI can perform almost miraculous feats of “intelligence.” Open AI’s ChatGPT 5 was able to pass the bar exam. The American Bar Association reported the AI “aced” the exam with a score “nearing the 90th percentile.” For years, IBM refined its Watson AI to be a medical expert. In 2020, the company shut down Watson for Oncology, its cancer AI, four years after a failed deployment at the prestigious MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The New York Times reported:

The problems were numerous. During the collaboration, MD Anderson switched to a new electronic health record system and Watson could not tap patient data. Watson struggled to decipher doctors’ notes and patient histories, too.

Physicians grew frustrated, wrestling with the technology rather than caring for patients. After four years and spending $62 million, according to a public audit, MD Anderson shut down the project.

Harvard Business School professor Shane Greenstein told the NYT, “They chose the highest bar possible, real-time cancer diagnosis, with an immature technology,” calling it a “high-risk path.” IBM has retreated a bit on the AI health care front, but they haven’t abandoned the field completely.

AIs do have a future in health care, and in law, writing, and other areas where their specific training codexes can be leveraged to save many hours of work. AIs write very good software code, for instance, though the user has to be extremely careful in how the specifications are provided. Feed an AI too general of a prompt, and the old problems will surface, producing hallucinations, bad math, and flawed logic.

But let’s skip past today’s battle, which I already said would be won by the motive for profit and power.

(If you don’t believe that national competition is a thing, read this from Scientific American: the Chinese government successfully tested space-based quantum communications, as in unbreakable encryption using quantum entanglement, in June of 2020. If this line of research bears more fruit, it could render all current forms of cryptography useless. Imagine an AI that could break any code.)

Let’s say we get past the “entertainment” value of chat bots, the “Eliza” of our time, and find real use for the technology. Boston Dynamics has connected ChatGPT to its advanced robot-powered dog “Spot.”

“This exciting development opens new possibilities for human-robot interaction and has potential applications in various industries, including security and elderly care,” the company added. Dangerous? Probably not, since you and I don’t have “Spot” in our living room. Potentially a game-changer? Not really, because we’ve known this was going to happen.

A fulfillment of a technological prophecy? Absolutely.

Pushing that future forward, we already have “telepresence” robots that help flesh and bone physicians conduct patient assessments, and even perform surgical procedures. If the doctor, instead of performing the procedure remotely, merely oversaw the AI perform the procedure, then one doctor (or physician assistant, or nurse) could supervise three, or five, or 10, AI-performed procedures. The limit to how many procedures could be performed would only be capped by how many devices we could manufacture (with robots doing the building).

Scarce procedures, like the sight-restoring cataract surgery YouTuber Mr. Beast (Jimmy Donaldson) recently funded for 1,000 who could not afford it, could become as commonplace as “take two aspirin.” Many surgeries, including gallbladder removal, cancer biopsies, dental surgery, nerve and joint reconstruction, which specialist surgeons perform by the dozen, could go from scarcity to plenty, culturally speaking, overnight.

But there’s a catch.

Isaac Asimov, who wrote the Three Laws, also wrote hundreds of short stories. One of them, in 1958, was titled “The Feeling of Power.” In it, a gentleman named Myron Aub had a skill nobody else seemed to possess. He could do math in his head. The dystopian society in Asimov’s tale (he’s always over the top) has computers making war with other computers; the military and political leaders use Aub to create a secret project on “human computation.” Sounds silly, but it’s the logical end of turning scarcity into plenty when the scarcity was based on human skill.

If doctors and lawyers, who hone their professional skills for years in the practice of medicine and law, now become users of AI technology built on the shoulders of generations of doctors and lawyers past, future professionals will become mere supervisors of computers.

If AIs running telepresence robots—or AI-powered autonomous robots—can perform 95 percent of the routine medical and legal work, leaving the “hard problem” five percent to humans, eventually humans qualified to handle the five percent will be harder and harder to find. In fact, it will take an effort of cultural will to identify, train, and separate the five percent to maintain that skill level.

The problem with that is one of statistics. In our society, it’s easy to find the best five percent of lawyers or doctors. They are the most sought-after in a large pool of doctors and lawyers. But if the 95% are not really practicing medicine or law in the sense that they do not, the five percent will be incredibly hard to identify, if they can be found at all.

A society that has eliminated scarcity on the basis of competency using AI will become a society enslaved to having to live with the failures of AI at the “edge cases” or the “hard problems” unless we also maintain a healthy population of humans who also do the work. But since AIs get paid nothing and have no material wants, that’s a hard economic nut to crack. The communists have a way to deal with it called authoritarian state control, but that inevitably leads to its own problems.

The drive for profit and power will move us inexorably toward Asimov’s version of the future. But we should take time to consider the actions of today. There may be some merit to the discredited “parable of the broken window.” Dealing with disasters and war are purely human issues. Dealing with the end of work as a scarcity is irreversible. It can only be dealt with by eliminating the levers that make work for us. Preserving some jobs for the sake of having skilled people with those jobs—in other words, limiting the use of AIs to a smaller population on purpose, and creating walled gardens where the AIs can operate, versus running amok in our world, may be the best answer to falling into Asimov’s paradox.

Example of AI hallucination: https://twitter.com/CPAutoScribe/status/1654210706500374528