Should Apple worry?

A history of antitrust cases yields some surprising results

Thursday, when the Department of Justice announced it is suing Apple for antitrust violations, the company’s stock dropped 4%. The main thrust of the suit is that Apple is being Apple—a walled garden by design—which creates a monopoly for the company to decide who, what, and how products are sold and integrated on its platform. But the only thing Apple is arguably better at than creating groundbreaking tech products (it literally created the touchscreen-based smartphone market), is defending itself in court. But Apple is not alone in the pantheon of big companies that have endured a government monopoly charge.

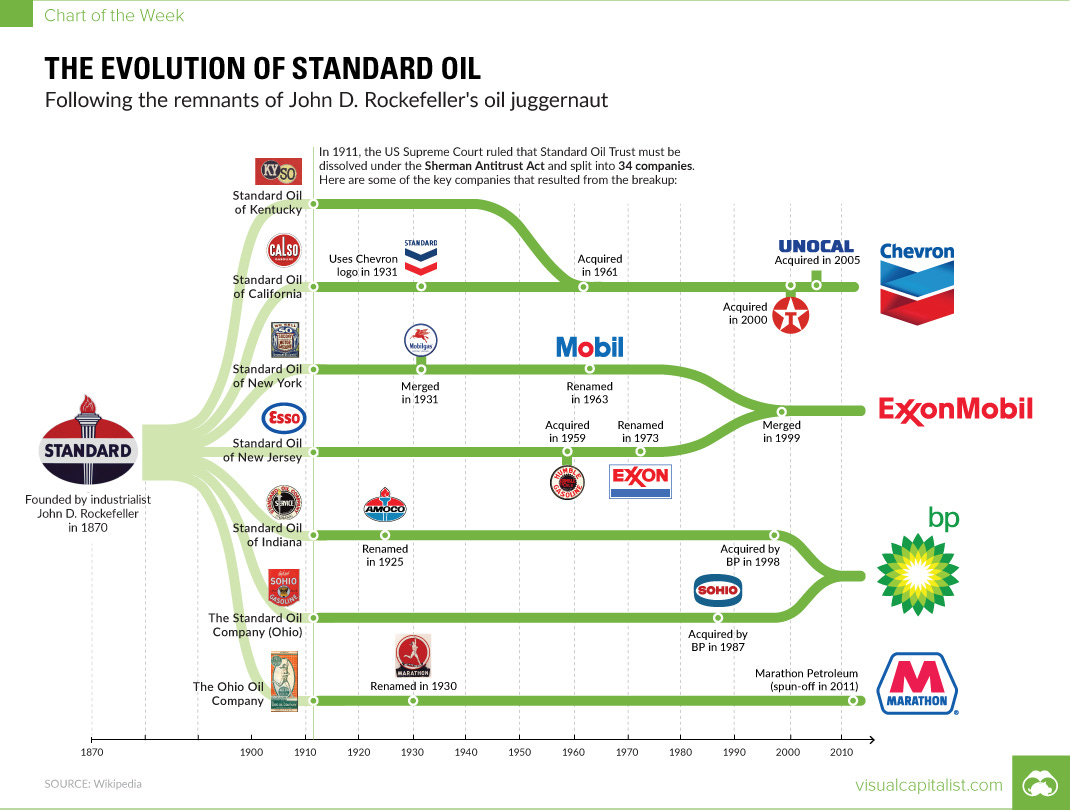

The U.S. government has a long history of suing companies that it deems “too big” or “too successful” in their market. In 1911, the government’s Sherman Act suit against Standard Oil went to the Supreme Court, which ruled that John D. Rockefeller’s company must be dissolved. It was broken up into 34 companies, some of which re-merged over the years into the recognizable brands you see today.

In the end, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Amoco/Sohio/BP, and Marathon are doing very well. At its peak, Standard Oil’s market cap was $1.1 billion, which would be in the neighborhood of $35 billion today. Immediately upon the breakup, the market cap fell to around $400 million. But the combined market caps of Standard’s successors is around $859 billion. Standard Oil controlled some 96% of the oil market, and had special deals with railroads that made it very difficult for competition to break their hold. Breaking up Standard was good public policy, but it was also very good for investors.

Apple’s market cap is $2.65 trillion, making it the second most valuable company (by market cap) in the world. The most valuable is Microsoft, at $3.19 trillion. Together, the market caps of these two companies combined (it’s not a great analogy but it’s fun to use) exceeds the GDP of every nation on earth save the United States and China. Microsoft was sued in 1998 by the DOJ for having a monopoly in PC operating systems (and also, at the time, internet browsers). The court ruled that Microsoft must be broken into two units, one for Windows OS and one for everything else. On appeal, Microsoft won the right to remain a single company, but it was forced to abandon its one-browser-to-rule-them-all practice.

Ultimately, the company was strengthened by the outcome. Opening the market to other browsers, such as Google’s Chrome, made Windows better, made interoperability better, and freed Microsoft to do other things better, like the Xbox. As a business strategy, running a walled garden may produce some good profit and growth for a while, but in the longer term, unless a company is continually extending into new gardens, it becomes truly burdensome, and the fruit rots on the trees. Microsoft learned this in the late 1990s and has never looked back.

In 1999, Microsoft had a market cap of $400.4 billion, or $740 billion in today’s dollars. It is valued at over four times that now. There is a long history of antitrust suits against companies that really needed to reinvent themselves and find new markets, while the cases themselves slogged along at the speed of snot going uphill in winter.

The Department of Justice sued IBM for attempting to create a monopoly in computing devices in 1952, resulting in a consent decree four years later, that forced the company to offer sale terms for all its computing machines that were previously only leased to customers, and constraining IBM from buying up all used equipment to create a single-source for its wares.

In 1969, the DOJ sued IBM once again, for “exclusionary and predatory conduct” that violated the previous consent decree. Of course, the computer market had evolved since 1956, from punch cards to reels of tape and even rudimentary spinning hard drive storage, and from consoles to cathode-ray terminals (though punch cards were still very common).

The IBM case went on for 13 years, and ended with IBM victorious (or the government finally giving up). From the Washington Post in January 1982: “‘There are no magic tools in a case like this,’ says Paul Saunders, 40, who has been on the defense team since 1973, ‘just a lot of hard work and preparation.’” In 1995, the Antitrust Division of the DOJ published its official memorandum on the case (available as a WordPerfect file, which as an inside joke is hilarious). Part of IBM’s victory rested on the government’s inability to prove IBM had the power it really possessed (for a while at least) in market terms.

The government’s assertion against IBM was crushed by a case involving Eastman Kodak Co. Kodak sought termination of two very old decrees dating from 1921 and 1954. They required Kodak to divest itself from acquisitions that made it both the primary producer and processor of film: they could not bundle photofinishing into the price of film or equipment. This gave a distinct advantage, over 80 years, to Fuji, Konica, Agfa and 3M. Kodak’s market share, while tremendous in film, was not so in photofinishing. The U.S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, ruled to terminate both decrees as they fulfilled their purpose in access to the market.

In 1992, the Supreme Court ruled, in a different Kodak case, that an antitrust suit by independent competitors who repaired Kodak copier equipment, could proceed. Four years later, a federal court affirmed a jury award of $72 million to the plaintiffs, plus a decree ordering Kodak to make spare parts available for sale at “reasonable, non-monopoly and nondiscriminatory prices” for ten years. Kodak was not strengthened by the multiple decrees and antitrust suits. But the company’s failure was not due to the lawsuits either.

Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975, but chose to sell that technology wrapped in high-end, scientific and niche markets, not to the public. They had a walled garden but let it die, choosing to cling to film.

In 1970, IBM’s market capitalization was $37 billion, or $295 billion in 2024 dollars. IBM’s current market cap is $174.95 billion. IBM was clearly more powerful in 1969 than it is today, but as the 7th most valuable company in the world, it is no slouch. IBM no longer engages in walled garden activities, but focuses on cutting-edge research and relevant products and services in cybersecurity, large-scale data, and AI.

Back to Apple. One of the company’s core competencies is the ability to aggressively defend its interests in court, then turn whatever comes against it into an asset. Epic Games, maker of the popular game Fortnite, sued Apple in August 2020 over Apple’s walled garden policies in access to the iPhone App Store. Epic had added a feature to its game that allowed players to pay Epic directly for in-app currency that can be used in gameplay. Apple objected, as all in-app purchases are required to go through the App Store, where Apple takes a 30% cut. Quickly, Apple removed Fortnite from its App Store, followed by Google.

The case went on for over a year, when a California judge ruled that Apple was not monopolizing mobile app payments by requiring developers to use its in-app purchasing methods. However, the judge also struck down Apple’s policy banning developers from steering users away from the in-app method using in-game notices in favor of developer-provided payment portals. Apple’s walled garden got a ding in it, but the wall was far from being breached.

Apple slow-rolled compliance with the 2021 order for three years, finally allowing links to in-app payments outside the App Store payment system in January 2024. And Apple isn’t making that “feature” free: it charges up to 27% commission on purchases made through the new outside link path. Epic CEO Tim Sweeney called Apple’s actions “bad-faith ‘compliance’” in a post on X/Twitter.

As for outcomes to the new antitrust case, the DOJ is not averse to levying a big fine on a company and then leaving things alone with minimal changes. Over the last 25 years, the Antitrust Division has levied 159 fines and penalties in excess of $10 million, from $925 million against Citicorp in 2017 to $107.9 million to Pilgrim’s Pride in 2021 for price fixing on broiler chickens. Many of these companies pled guilty or entered into consent decrees to preserve their reputations and keep the stories out of the public headlines. But Apple doesn’t have that option. It’s also not in the company’s DNA to admit wrong (ever). There will be no guilty plea or quiet settlement.

Apple’s commitment to a walled garden is not simply based on market power, domination, and control. It is a company aesthetic: the Apple Way. The company argues that it’s ultimately better for consumers to have a simple way of doing things. It argues that the iPhone ecosystem is more secure, its payment system less prone to fraud, and its App Store safer from hackers and other nefarious organizations than what the government would force by breaking up the walled garden.

But Apple knows, internally, that its version of utopia doesn’t exist, and its protective caretaker attitude is largely a public-relations sham. Documents obtained by Epic in discovery show that Steve Jobs long ago intended to “lock in” consumers to the Apple ecosystem, to keep rivals like Google out. Apple’s behavior in the market belie the consumer protection image, and support the “lock in” argument, despite its long history of keeping things in its aesthetic. Money is, after all, not an aesthetic, but a fungible thing, which to charge 30% for the privilege of paying a developer so Apple can preserve its control seems predatory or at least excessively greedy.

If Apple wants a walled garden that encompasses money, it should print its own.

(An aside: Disney, from 1968 to 2014, printed “Disney Dollars.” These are still accepted at selected locations in Disney parks—they used to be accepted at Disney stores in malls—but they are worth far more as collectibles. In the late 80s, I had lunch with a group of engineers who worked for the company that made the printing presses Disney used. They had some interesting but crazy ideas for the perfect crime, since it’s not illegal to counterfeit bills that are not fiat money. Of course, it’s fraud to use those bills, but the Secret Service wouldn’t be waiting at the cash register to catch you.)

Let me answer the question in the headline: Should Apple worry? No. It should not worry. In 2022, App Store developers generated $1.1 trillion in total billing, according to the company’s press release. Apple claims that over 90% of those billings went straight to developers, with no commission collected by Apple. In 2023, consumers spent $89.3 billion using the App Store, with TikTok the biggest grossing app.

Apple is already planning to expand its roll out of non-Apple payments, and certainly has a plan to turn that into a service cash flow. The company is well prepared for whatever DOJ is going to throw at it, but will fight to the bitter end any proposal to break itself up.

However, what will result here is going to be better for consumers. Apple is not entitled to a walled garden for money, as I wrote above. Its products should benefit—and that’s Apple’s allure—from a unique aesthetic, including user interfaces and ways to pay for things. Apple Pay transformed digital payments and EMV, mostly for the better, introducing the U.S. to cashless society (which has been in Japan and Europe for some time). This should not be overlooked.

Breaking Apple Pay and the App Store out into separate entities would not serve consumers, as these companies would, by definition, have to compete for customers and would not be allowed as tight an integration as a single unified Apple can do. Ultimately, the smartphone market and payment infrastructure would be less safe, at least in the short term, by such a move. I think the government realizes this, despite its aggressive language in the antitrust suit.

In Microsoft’s case, the hardware-software integration was not in play. In IBM and Kodak’s cases, it was. In Apple’s case, hardware, software, consumers and developers are all in play. Whatever the outcome, the DOJ’s move has already improved things for consumers, by forcing Apple to think outside its walled garden.

Great summary on the case and the history!

As someone who's been developing iOS apps since the beginning, I hope that the gov't has some success in pushing Apple to open up the platform to alternative app stores, as the EU is forcing them to do with the Digital Markets Act (and Apple's providing the best examples of passive-aggressive malicious compliance that I've ever seen).

The fundamental issue at play for us developers is that Apple is selling iPhones for full price to consumers and then telling those customers what they can and cannot have on the devices that those customers own. I currently have a research study on indefinite hiatus because Apple decided that what were doing with a fully informed and consented research population (overseen by a university institutional review board) wasn't something that they would allow, and they denied access to the API (Family Controls) that their own internal devs are free to use as they like.

You mention in your piece that this is the "Apple Way". That's not entirely true. iOS was the first platform where Apple was able to actually exercise this level of control (empowered by cryptographic code signing and Apple controlling all the keys). The Mac prior to iOS was a remarkably open platform with a thriving community of commercial and "indie" software developers innovating and serving happy customers. (Many of these innovations were later usurped by Apple and incorporated into their own products - search for "apple sherlocking".) In the decade since the introduction of iOS, we've seen Apple increasingly try to exert the same control it has on iOS on the Mac platform using the same code-signing technologies.

Like you, I'm skeptical that the US gov't will do much to Apple here. Using the Microsoft case as an example, the court case will last YEARS, and it's more likely that some third party development (a move away from apps to browser-based interactions, generative AI becoming the default user interface for computing devices, VR, etc.) will do more to depower Apple than the DOJ.

Still, as a developer who has wasted significant amounts of time dealing with Apple's nonsense over the past decade and a half, the greatest good that this case could achieve is breaking Apple's monopoly on application distribution and allow other app stores on the device. This would give customers an actual choice for where they purchase their software, and it would put pressure on Apple to actually quit collecting rents on their App Store, and actually make it a compelling place to FIND (good app discoverability on the App Store has been broken for over a decade) and purchase software from the third-party developers working hard to produce it.

Take a look at what Steam and other alternative software markets have done for the PC. There's no reason - other than Apple's greed - that innovation and competition cannot exist on iOS devices, AND Android devices, as Google's been more closely emulating Apple's behavior in the past couple of years with the Google Play market. Epic sued them and found more success in their suit against Google.

Handheld computing is too valuable of a form factor to let a couple large entities dictate and monopolize which applications will be allowed on them.

I remember "Too Big to Fail" and I think what you are talking about goes along that, and what has happened. I think when companies get so big perhaps new laws should be applied. Spin-offs used to be a thing now conglomerates are the thing and causes monopolistic practices. Transparency is the only thing to keep "what is happening" from happening. I could understand, and I hope for, laws where a set market share, or a company net worth, would kick in to stop this from happening. Predatory practices are the villain and laws could be written to make these practices apparent.