Don't whitewash Black History

The shameful side of history should be remembered.

Today, I’ve got something a little different. It’s February and February is Black History Month. In recent years, there has been a movement in some quarters toward whitewashing, for lack of a better term, America’s racial history.

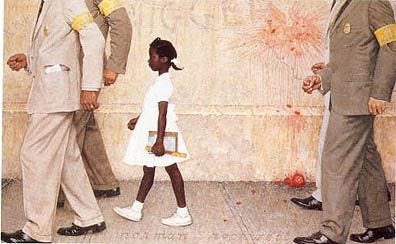

Among the books that have been challenged in school libraries in recent years are books about Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ruby Bridges, a black girl who was the first student to integrate New Orleans public schools in 1960. Books such as these are historical fact, but some groups such as Moms For Liberty see them as problematic.

The first complaint lodged under a Tennessee law aimed at preventing the teaching of Critical Race Theory in 2021 was against several books that included the stories of King and Bridges. The complaint alleged that the books contained “anti-American, anti-White and anti-Mexican teaching.”

Per CNN, Moms for Liberty’s Robin Steenman also objected to a book that contained a famous Norman Rockwell painting of then-six-year-old Ruby Bridges and said that teachers shouldn’t lead discussions about the book’s content. (I’m not an art aficionado but I do love Rockwell’s work.)

“There’s no need to emphasize it,” Steenman said. “Just, you know, if they want to read ‘this book has a famous painting,’ fine. And then just move on.”

Chris Rock once joked, “Black History Month is in the shortest month of the year, and the coldest—just in case we want to have a parade.”

Often, it seems like Rock was kidding on the square.

The issue of black history came up again just a few weeks ago when Nikki Haley neglected to mention slavery as the cause of the Civil War when a probable plant asked about Southern history at a New Hampshire campaign stop.

“I think the cause of the Civil War was basically how government was going to run — the freedoms and what people could and couldn’t do,” Haley said, neglecting to mention that the freedom in question was the freedom to own other human beings.

That’s more than a minor omission.

If you happen to be one of the Confederate apologists who deny that slavery was the cause of the war, I urge you to read the words of the secessionists themselves. The Declarations of Causes of the seceding states are available online at the American Battlefield Trust. The documents make clear that the state right that drove secession was slavery.

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery-- the greatest material interest of the world,” Mississippi secessionists wrote.

I often hear people say, as Steenman did, that we just need to move on. After all, slavery ended 150 years ago. I used to be one of those people.

I can admit now that I was ignorant. The good news is that ignorance can be cured with education.

Slavery may have ended in 1865, but racial discrimination did not. History talks a lot about the Civil War but pays less attention to the post-Reconstruction period. Many know about Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, but fewer know about how the disputed election of 1876 led to the removal of federal troops from the South and an amnesty for Confederates put failed secessionists back in charge of the Southern states. Once back in charge, the Confederates implemented Jim Crow segregationist laws that lasted well into the 20th century.

It may be true, as I’ve heard many times, that there are no living former slaves. The same statement cannot be made about people who lived under separate-but-equal laws. There are a great many Americans who have personal memories of segregation, just as Ruby Bridges, now 69 years old, does.

Schools in Georgia were integrated within my own lifetime, if barely. I was in one of the first few integrated elementary schools in my county. The building had formerly been one of the county’s segregated black schools, but my class was about half black and half white.

As it turns out, some schools were segregated long after that. Cleveland High School in Cleveland, Mississippi became the last school to be desegregated by a court order in 2016. Yes, you read that right.

For more than 200 years, Americans kept blacks separate and did everything that they could to prevent assimilation. Now, over the past couple of decades, the script has been flipped and the same factions that fought for segregation are now screaming that the country should “move on” and not dwell on the centuries of slavery and segregation.

It’s a nice sentiment, but it’s not realistic.

I’m also not sure how sincere it is. Many of the same people complain about erasing history when Confederate statues are removed from places of prominence. So should we gloss over the sordid history of slavery and discrimination but honor the people who tried to rip apart the Union to preserve the South’s “peculiar institution?” That doesn’t seem right either.

We shouldn’t erase our history, no matter how uncomfortable it makes us, but it should be in the proper context. Slavery was evil, but it doesn’t have to define us 150 years later. It also shouldn’t be swept under the rug as if it never happened. Our history made us who we are today and we live with its legacy.

Likewise, we shouldn’t whitewash the Confederacy. The Confederates were people of their time. Some were good people, but in the end, they served an evil cause. Both sides of their character should be explored, but the truth is that people who fought to destroy the Union don’t deserve places of honor in modern America.

We need to educate young Americans about slavery and what came after. We need to remember the racism of the past to avoid it in the future.

Growing up in Georgia, I never heard the stories of massacres of blacks in places like Tulsa, Oklahoma, Rosewood, Florida, and Camilla, Georgia. We weren’t taught about the Tuskeegee study, in which black men were denied treatment for syphilis. This experiment went on into the 1970s. The gaping hole in my historical knowledge wasn’t filled until I was an adult. I suspect that the gap would have pleased Robin Steenman.

In closing, I’m going to tell you a story. I used to drive across the Broad River in northeast Georgia going to the University of Georgia and later to jobs in Athens. For years, I noticed a historical marker near the bridge over the river.

The marker tells the story of Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, an army officer and WWII hero who was driving home from Fort Benning to Philadelphia with several other soldiers. The men, all black, drove through Athens early in the morning of July 11, 1964.

As they drove through Athens, they attracted the attention of several local members of the Ku Klux Klan. The klansmen chased down the car full of soldiers and fired shotguns into the car as it crossed the Broad River bridge, killing Penn.

The klansmen were arrested soon after and tried before an all-white jury. They were acquitted. It seems that killing black folks wasn’t considered a crime by many white citizens.

But the story doesn’t end there. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been passed recently and the klansmen were charged with federal crimes for the killing. The two trigger-men were convicted and sentenced to 10 years, but several others were acquitted. (You can read the full details of the story in a blog post that I wrote back in 2012.)

I tell this story for a couple of reasons. First, the conviction of Penn’s murderers was a monumental moment in civil rights history. It marked the moment when racist vigilantes learned that they could be held accountable by juries outside their home states, juries who didn’t accept the morality of separate-but-equal racism.

The story of Lemuel Penn is a reminder that the struggle for black equality - and the fight for the right of blacks to life - didn’t end with abolition. Penn died seven years before I was born and less than 20 miles from where I grew up. For me, learning about Penn’s murder drove home the nearness of the segregation era both in terms of time and geography.

As a footnote, Fort Benning, where Penn and his comrades had been stationed, is one of the bases that was recently changed. The post was named for a Confederate general and has now been rechristened “Fort Moore” in honor of Lt. Gen. Harold Moore and his wife, Julia. The new name, honoring the man portrayed by Mel Gibson in the movie, “We Were Soldiers,” is appropriate.

America is different now. The Moms For Liberty challenges in Tennessee failed. Nowadays, we don’t throw out history just because it’s uncomfortable or reflects poorly on our forebears. We are strong enough to deal with our past, warts and all.

Nikki Haley, who botched the softball Civil War question in December, also got a mulligan on “Saturday Night Live” last weekend. In the opening skit, a voter asked her if the main cause of the Civil War “starts with an ‘s’ and ends with a ‘lavery?’”

“Yep, I probably should have said that the first time,” Haley laughed.

America has changed a lot in my lifetime. We’ve come a long way racially, but we need to remember where we came from.

February days are still dim, short, and cold in New Hampshire. Thank you David for shining some light.